Understanding Bitcoin Privacy with OXT — Part 3

Introduction

With the foundational concepts of chain analysis introduced in Part 1 and Part 2, Part 3 will discuss the methods for undermining chain analysis.

In this section we will present the following:

- defeating heuristics for change detection in simple spends

- creating an ambiguous transaction graph with equal output coinjoins

- undermining the CIOH with coinjoins

The UTXO Ownership Model & Ambiguity Of Simple Spends

Previously, we introduced change detection heuristics for simple spends with 1 input and 2 outputs. We assumed that the transaction included a payment and change output.

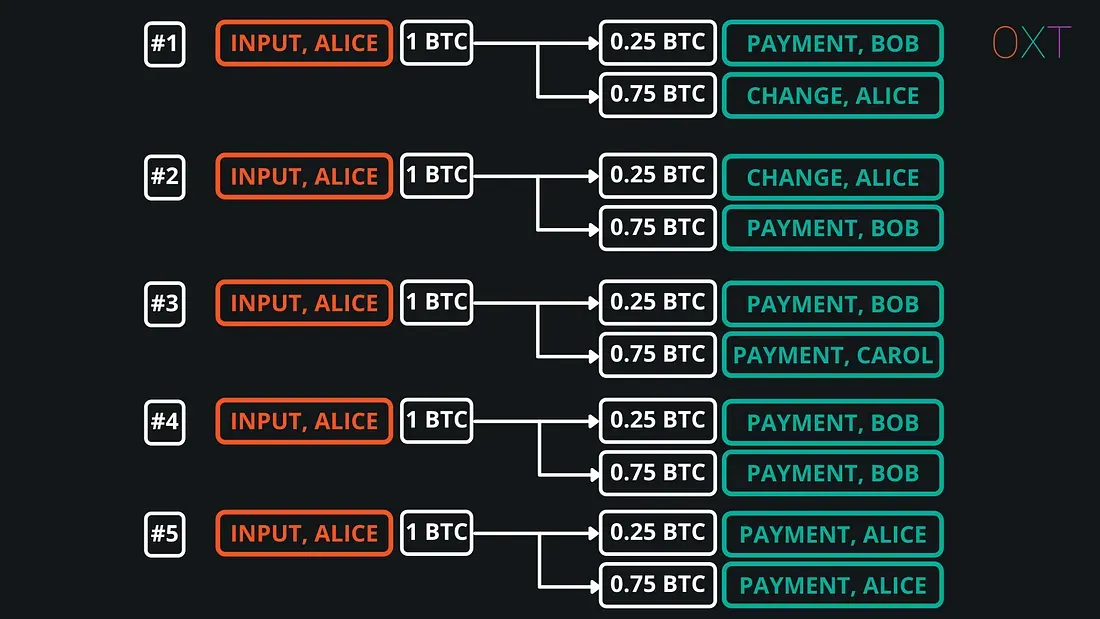

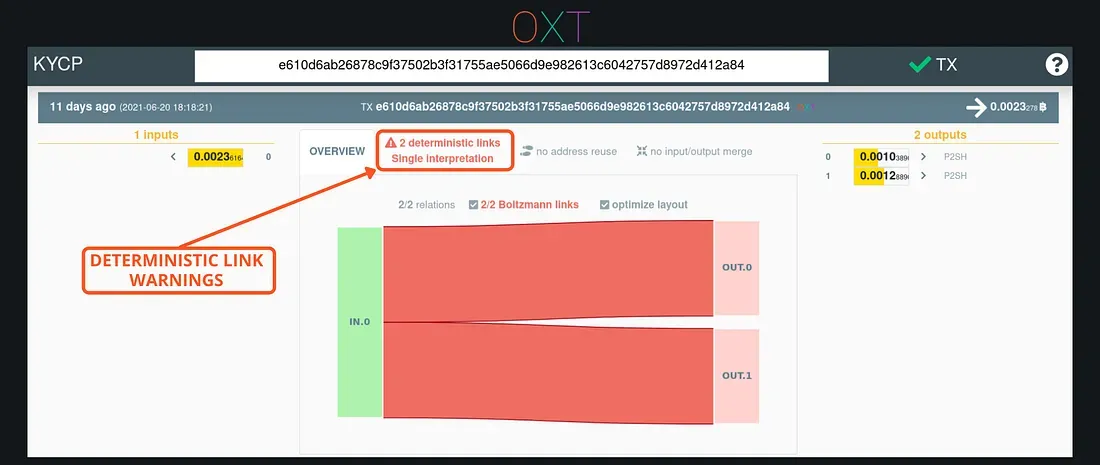

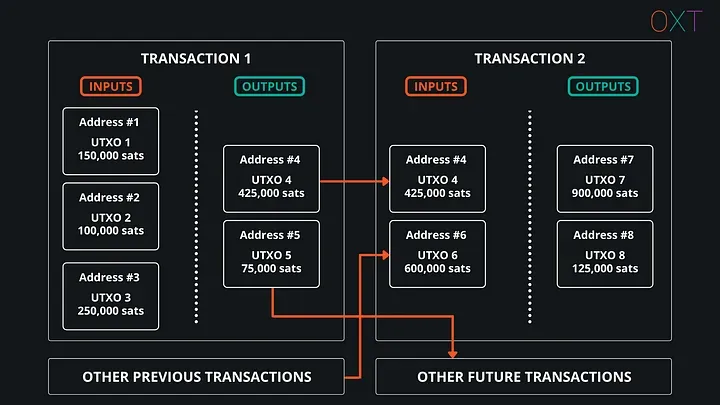

In reality, a simple spend has many additional interpretations based on the UTXO “ownership model”. The ownership model attempts to assign ownership to the inputs and outputs of a transaction. The complete ownership interpretations for a transaction with 1 input and 2 outputs are shown in Fig 3.1.

Each of these interpretations must be considered by an analyst, especially when only applying internal transaction data. Interpretations can be eliminated when accounting for additional wallet fingerprinting, normal wallet behavior, and typical user behavior.

Typical user behavior makes interpretations 1 and 2 most likely. Interpretations 3 and 4 are possible, though many bitcoin wallets to do not have batch spend functionality. Interpretation 5 is rare due to extra fees paid and UTXO set bloat.

The application of external transaction data such as outputs sent to centralized services or reused addresses, can be used to eliminate interpretations. Due to the concentration of the bitcoin transaction graph around centralized services and patterns of normal user behavior, these full interpretations are rarely considered in practice.

Defeating Change Detection Heuristics

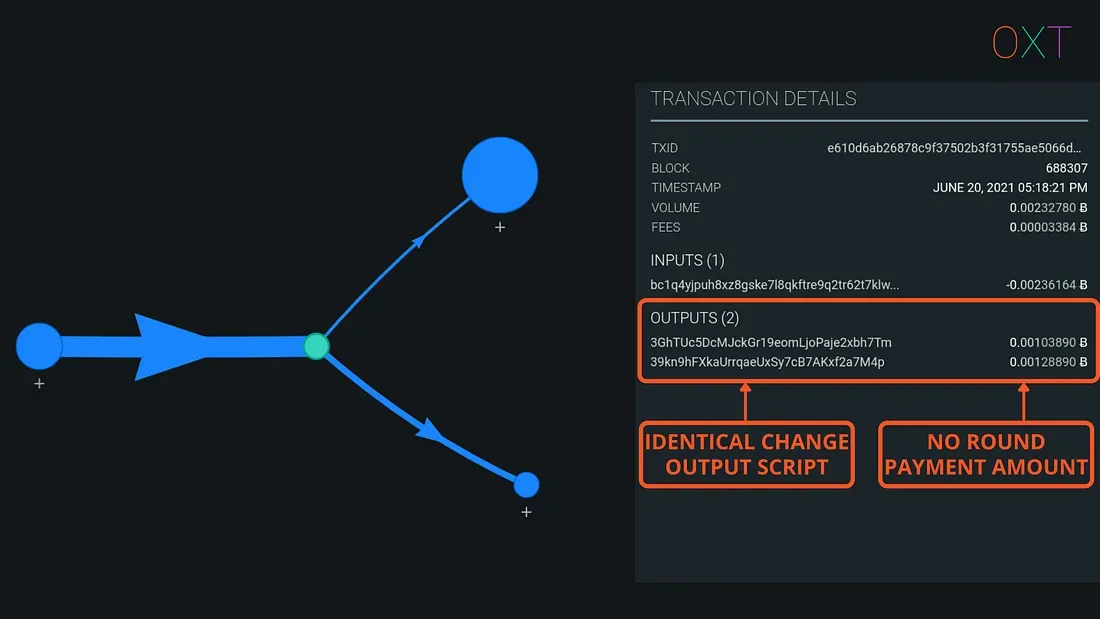

Transactions can be made more ambiguous by wallet software that aims to defeat the heuristics for change detection presented in Part 1. When taken in isolation, the transaction below is an example of a “maximally” ambiguous simple spend.

Round Number Payment Heuristic Defences

The payment amount is determined by the user. If a user selects a round payment amount, it is difficult for a wallet to protect against this heuristic in a simple spend. For most true payments (priced in fiat), this heuristic is less likely to apply. The example in Fig 3.2 above does not have a round number payment amount and maintains protection against this heuristic.

Identical Change Output Script Type

The example transaction has identical output script types for both outputs so the unique script output heuristic does not apply. This helps to maintain ambiguity and makes change detection more difficult.

Randomized Change Output Position

To further increase the ambiguity of this wallet’s behavior over a series of transactions, wallet software must randomize the change output position. Alternating the change position between output 0 and 1 would make the automated tracking of wallets like the activity shown in Fig 2.8 more difficult.

Evaluate the Transaction Including External Transaction Data

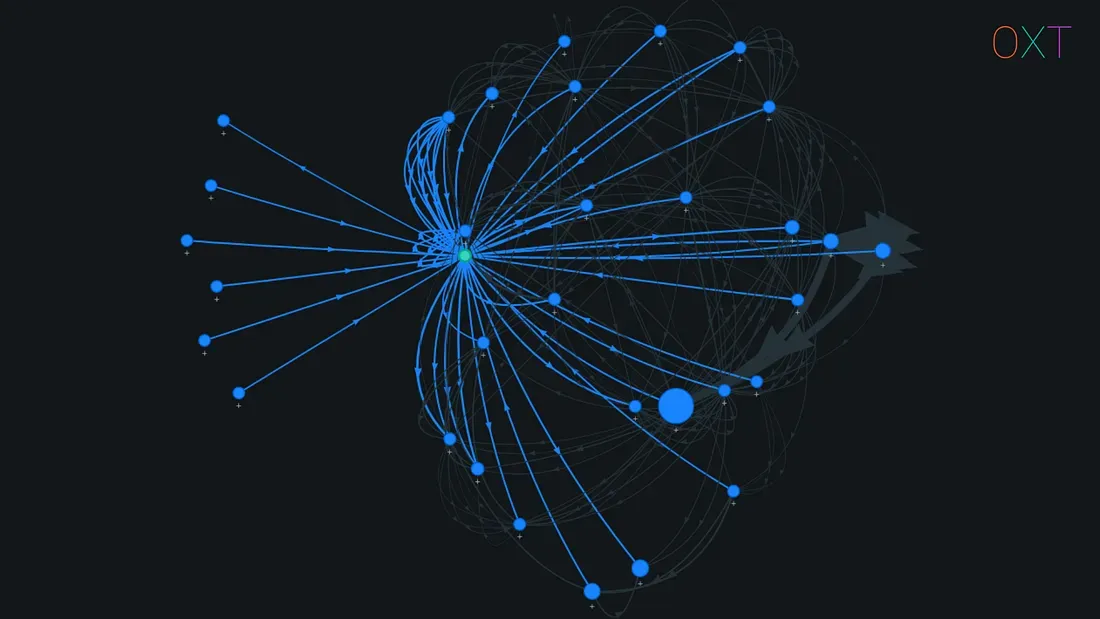

OXT’s transaction graph shows relative UTXO and transaction amounts by varying line weights. In this way, expanding the transaction graph automatically includes some external transaction data.

Based on the transaction graph and future UTXO spending, which output might be the payment? Do the addresses in this transaction have any previous history of reuse?

This is a perfect example of how external transaction data can be used to aid in determining payments and establishing a change output. Expand the transaction graph or follow the future UTXO spending to verify your payment/change assumption.

UTXO Flows And Deterministic Spends

Identical change output scripts and randomized change positions can be applied by wallets to maintain the ambiguity of simple spends, but they do not address the fundamental link between inputs and outputs consumed in a transaction.

A link always exists between a transaction’s inputs and outputs. These intra-transaction UTXO relationships can be thought of as “flows”. Where the BTC consumed by input UTXOs are transferred to the output UTXOs.

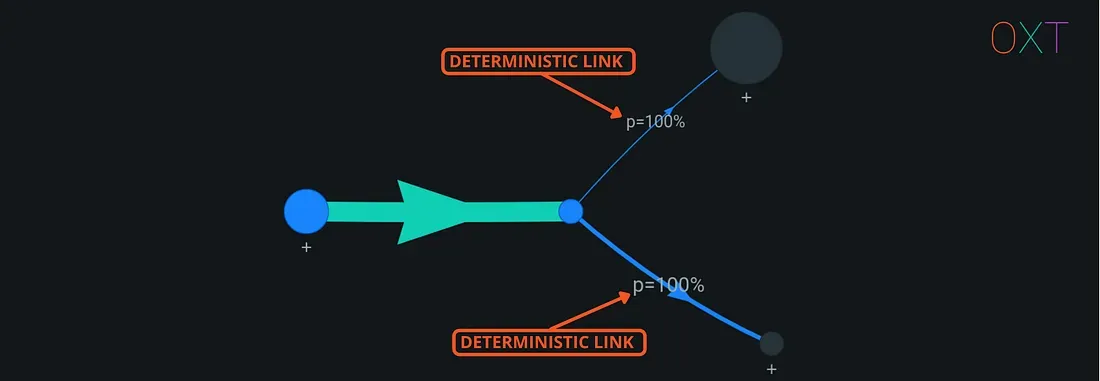

In the case of a simple spend (1 input and 2 outputs), the single input must have been used to pay both outputs. A simple spend’s intra-transaction flows only have a single interpretation. As a result, the link between the single input and each output is mathematically deterministic (certain).

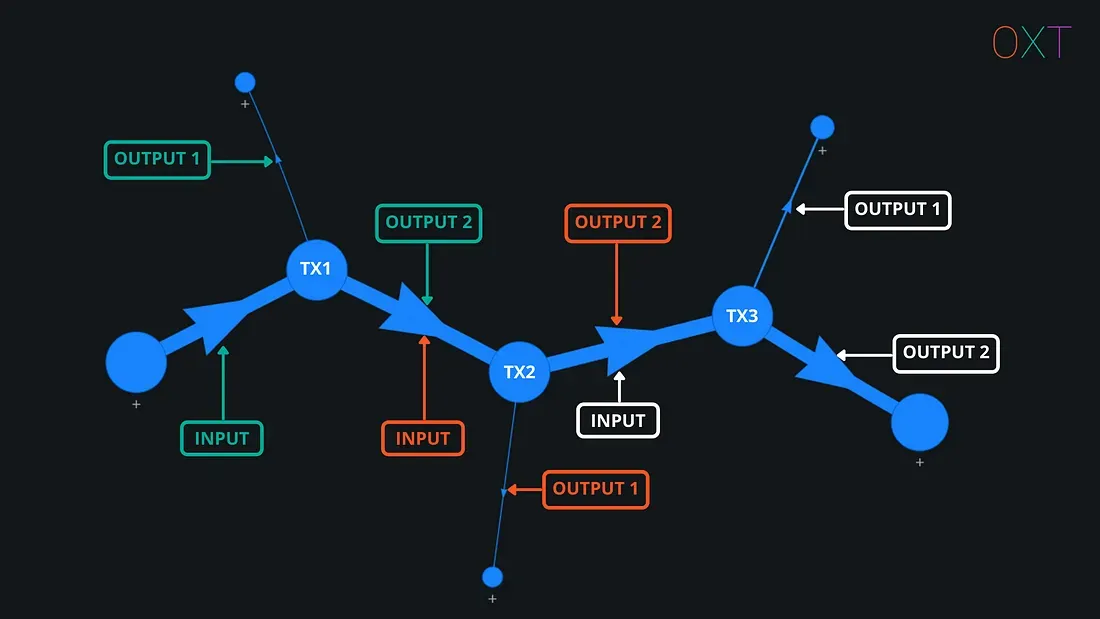

The link between inputs and outputs can be displayed on the OXT transaction graph by selecting an input or output. The transaction visualizer at kycp.org also shows the intra-transaction links.

Breaking Links — Non Deterministic Transactions

Though UTXO ownership ambiguity always exists, the UTXO ownership model cannot be relied upon to obfuscate on-chain BTC flows. Without breaking deterministic links and introducing ambiguity into the transaction graph, bitcoins remain “traceable”.

Breaking deterministic links and creating on-chain ambiguity requires a specific transaction structure. Determinism is dependent on the number of transaction inputs, outputs, and the BTC amounts of each UTXO.

By themselves, transactions with multiple inputs and outputs can create a noisy transaction graph. These types of transactions are not easily interpreted without special tooling or considerations.

Despite the noisy transaction graph, deterministic links between UTXOs of transactions with multiple inputs and outputs can still be evaluated. Kristov Atlas was the first to introduce this concept in his “CoinJoin Sudoku” advisory and algorithm.

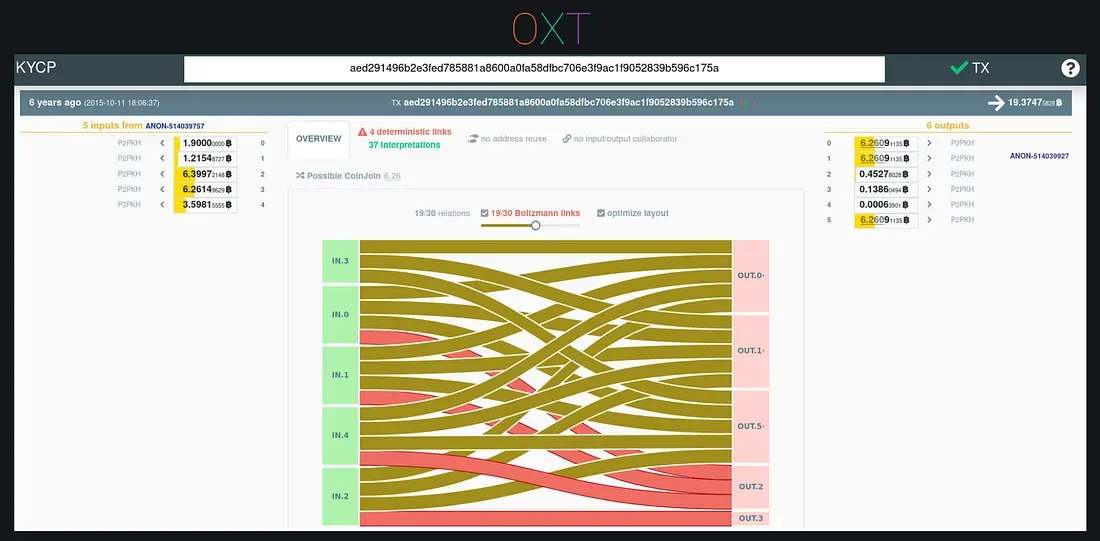

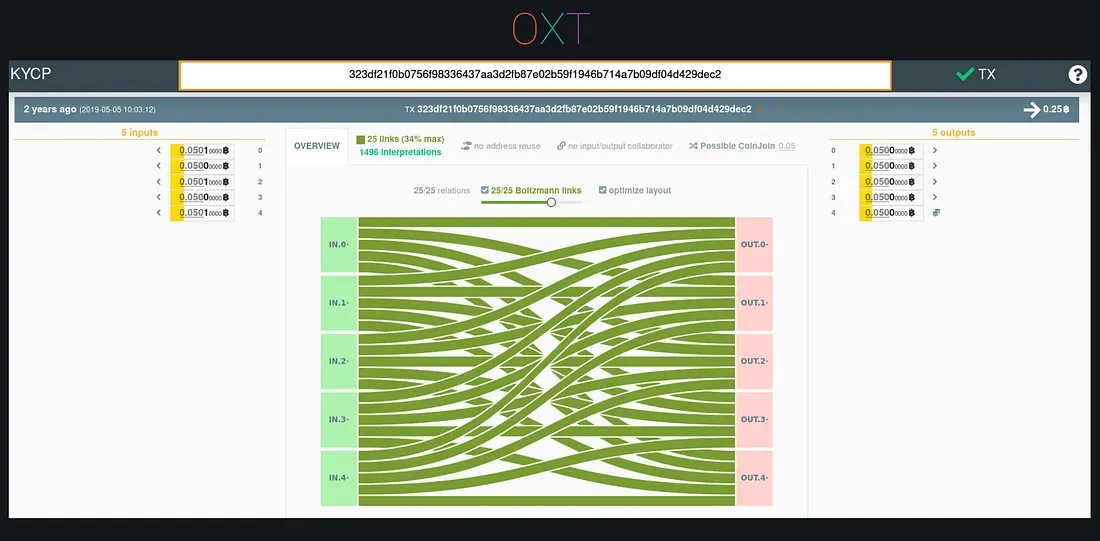

In a coinjoin, users pool their funds and collaborate to construct a transaction. Typically by creating a transaction with equal output amounts. The CoinJoin Sudoku algorithm uses a branch of mathematics called subset sum analysis to evaluate transactions for “common ownership” of inputs and outputs.

A discussion of these maths is beyond the scope of this guide, but the important takeaway is that a naively constructed coinjoin transaction can be evaluated for deterministic links.

Today, the coinjoin sudoku concept has been extended with the Boltzmann algorithm created by the OXT lead developer, LaurentMT. Boltzmann uses the CoinJoin Sudoku concept to evaluate transactions for several privacy related metrics.

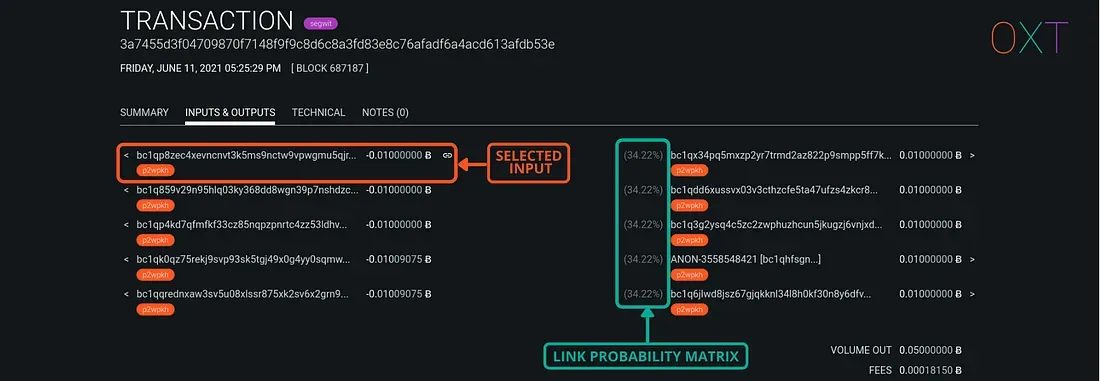

For properly constructed coinjoins, a link between inputs and equal outputs still exists, however these links are probabilistic not deterministic. The Boltzmann algorithm calculates a Link Probability Matrix (LPM) for the relationship between a transactions inputs and outputs.

A transaction’s LPM output can be found on the TRANSACTION page on OXT. In the INPUTS & OUTPUTS tab, the link subset between an input and each output can be seen by clicking the “CHAIN ICON” to the right of the desired UTXO.

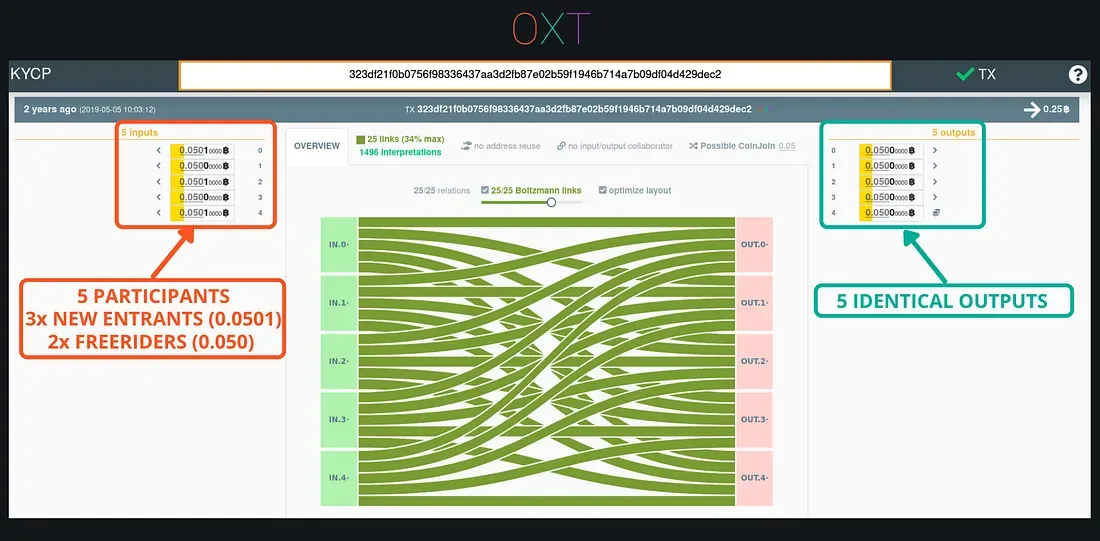

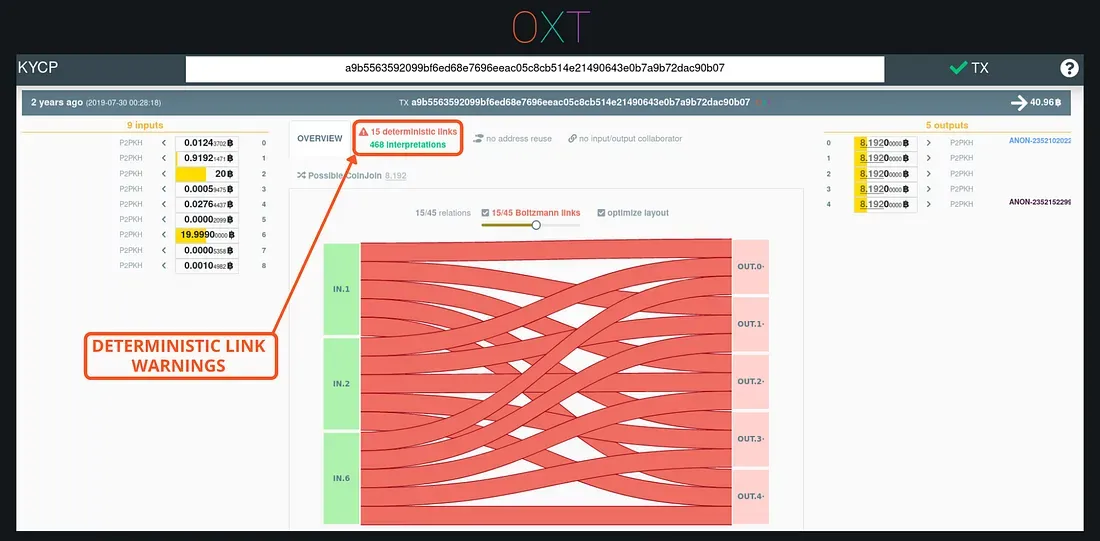

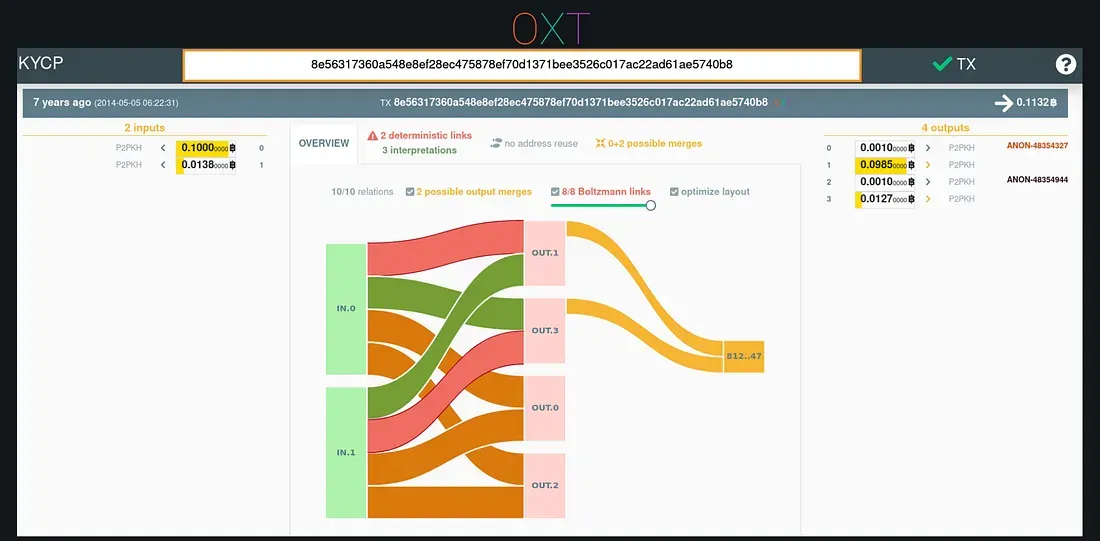

The LPM for selected UTXOs in evaluated transactions can also be found by selecting inputs and outputs on the OXT Transaction graph (see Fig 3.3). A visual of the full LPM produced by Boltzmann’s algorithm can be found at kycp.org.

Entropy — Equal Output CoinJoins And When Is It Appropriate To Apply The CIOH

In an equal output coinjoin, multiple users collaborate to create a transaction that pools their funds and breaks the deterministic links between their transaction input and equal output.

By including multiple users, these transactions also break the CIOH. Assuming inputs to transactions that could be coinjoins are controlled by a single wallet could result in a false positive wallet cluster by the CIOH.

To avoid this an analyst could apply an equal output heuristic to transactions that may be coinjoins. However, all transactions having multiple equal outputs are not necessarily coinjoins. If constructed naively, transactions with multiple equal outputs may still have deterministic links between inputs and equal outputs, which is evidence that a transaction is not a coinjoin.

Instead of incorrectly clustering a transaction or naively excluding transactions with identical outputs, analysts can truly evaluate transactions for coinjoin properties using Boltzmann.

Boltzmann effectively uses subset sum analysis to ask the question: Are there multiple ways (interpretations) a transaction’s inputs could have paid its outputs?

If a transaction has multiple intra-UTXO flow interpretations, Boltzmann will score the transaction’s entropy greater than or equal to 0. The concept of entropy originates from a thermodynamic mental model. In this model, the number of interpretations can be thought of as microstates of the overall transaction macrostate.

Entropy can be seen as a metric measuring the analysts lack of knowledge about the exact configuration of the transaction being observed.

Transactions with entropy have coinjoin properties and broken deterministic links. Coinjoin properties are evidence that a transaction has multiple users contributing inputs to the transaction. Conservatively, the inputs to transactions with entropy should not be clustered by the CIOH.

KYCP Transaction Interpretation

KYCP includes a significant amount of transaction information including address reuse across the transaction, deterministic and probabilistic links, and input and output merges. The example transaction above is a dark wallet coinjoin transaction. The deterministic links for equal outputs are broken, but deterministic links still exist between the inputs and “change outputs”. Also note that output 1 and 3 are sent (merged) into the same future transaction. Indicating that the same users/wallets are mixing together again.

CoinJoins — Equal Output (Encryption) vs. PayJoin (Steganography)

Equal output coinjoins have a unique on-chain footprint that can be identified by the presence of multiple equal outputs. But the flows across the transaction for equal outputs are not deterministic. If an analyst knows they are observing a coinjoin, they must consider the user they are attempting to track controls one of the many equal outputs. In most cases this is enough to stop an analyst in his tracks.

When an analyst encounters an equal output coinjoin, they know a privacy technique is being used but cannot reliably interpret the transaction. In this way, equal output coinjoins are similar to encryption. Observers of encrypted messages know a message exists (can observe the coinjoin) but cannot decipher the message (reliably interpret the flows across the transaction).

The other type of coinjoin is called payjoin or pay-to-end-point or Stowaway in Samourai Wallet. Payjoin transactions consist of a collaborative transaction between the user making a payment and the user receiving a payment. On the blockchain, many payjoins have no discernible patterns or applicable heuristics.

In effect, payjoins are indistinguishable from a normal transaction where a user spends multiple UTXOs. Without any distinguishable on chain transaction footprint, an analyst may incorrectly apply the CIOH to these types of transactions and incorrectly assume each of the inputs are controlled by the same user.

In this way payjoin transactions are a steganographic technique. Steganography is the process of hiding a secret message (the fact that a coinjoin has occurred) within otherwise normal appearing data (a normal transaction spending multiple inputs). Because payjoins do not have any reliable on-chain footprint, they often result in false clusters by the CIOH.

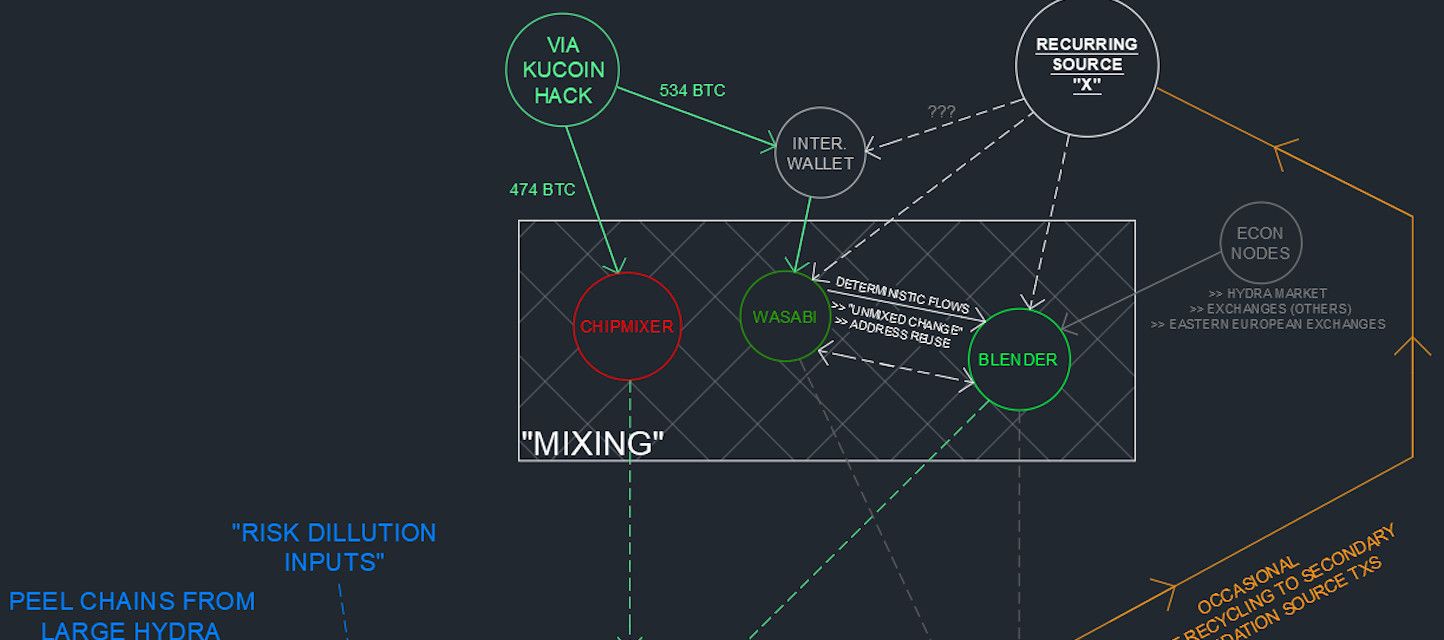

Other Techniques — “Breaking” The Transaction Graph

Custodial tumblers, often referred to generically as mixers, are one of the oldest privacy techniques employed at the application layer. The purpose of custodial tumblers is to act as a swap service. Users deposit coins to the tumbler and (hopefully) receive different UTXOs with a new transaction history in return. Ideally, the swapping process results in a “broken” transaction graph that severs the link between a user’s deposits and withdrawals.

This techniques also popularized the concept of “taint”. Where tumbler users may unknowingly receive UTXOs with some “problematic history” as a part of their swap. Interested readers can see our evaluations of two of the largest custodial tumblers (ChipMixer and Blender) from our investigation of the Kucoin Hack.

Additional privacy enhancements such as coinswaps aim to break the transaction graph in a non-custodial way. These techniques are still in their infancy. Without additional mitigation, these theoretical swaps will suffer from the same “taint” swapping issues as custodial tumblers. This section will be updated as additional techniques are deployed.

Review

In Parts 1 and 2 we introduced the fundamentals of chain analysis including change detection, transaction graph analysis, and the common input ownership heuristic.

In Part 3 we introduced the many tools capable of defeating the main heuristics of chain analysis.

Change detection heuristics can be defeated by avoiding round payment amounts, creating transactions with identical change output script types, and randomizing change output positions.

Equal output coinjoins are collaborative transactions involving multiple users. By breaking deterministic links these transactions create ambiguous transaction graphs. By involving multiple users, they defeat the CIOH.

Payjoin transactions are also collaborative transactions. They involve the payer and payee in creating a transaction and have the same transaction fingerprint as a normal multi-input spend. Without an identifiable fingerprint, these transactions defeat the CIOH.

Part 4 discusses:

- Analyses needing a “starting point”

- The privacy implications of sending and receiving payments

- How existing privacy techniques can mitigate many of the issues discussed throughout the guide.